:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Sound of Water (mizu no oto)

***** Location: Japan

***** Season: Non-seasonal Topic

***** Category: Earth

*****************************

Explanation

mizu no oto 水の音

ever since Basho wrote his famous haiku and it has been translated into other languages, this formulation has fascinated haiku poets worldwide.

Let us look at some of the problems involved with it.

Just googeling with "mizu no oto" and "haiku" gives more than 16.400 hits, in June 2006. So it is an important topic.

shared by Ponte Ryuurui

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

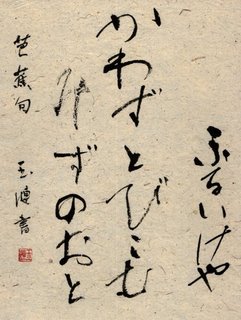

古池や蛙飛び込む水の音

furu ike ya kawazu tobikomu mizu no oto

........................... in normal Japanese

as Shiki put it

古池に蛙が飛びこんでキャブンと音のしたのを聞きて芭蕉がしかく詠みしもの

furuike ni kawazu ga tobikonde kyabun to oto no shita no o kiite Basho ga shikaku yomimashita mono

furui ike ga arimasu (furuike ni)

kawazu ga tobikomu to

mizu no oto ga kikoemasu

there is an old pond

and when the frogs jumped in

(I heared) the sound of water

or leaning on Hasegawa Kai:

(when) the frog jumped in

(I heared) the sound of water ...

(that made me remember, I was sitting by)

the old pond

Cause and Effect .. and the CUT MARKER

Gabi Greve

When I read this, I see a description of a simple situation, which I can experience here in my rural Japan every day now in May, since the frogs are out and active ...

whether Basho lived through this situation as a personal experience

or

imagined the whole situation ... I do not know.

And the haiku itself does not give me a hint to answer this.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

old pond — frogs jumpes in — sound of water

Translated by Lafcadio Hearn

FROG, kaeru, kawazu as a kigo

One Hundred Frogs, a translators nightmare ...

http://www.haiku-plus.de/englisch/haiku-e.html

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Direct translation (chokuyaku) :

mizu no oto ... (the, a) sound of water

grammatical chokuyaku :

mizu no ... of water

oto ... a sound ... of water the sound ... the sound of water

bad chokuyaku example :

mizu .. water

no .. of

oto .. sound ... > water of sound

since there is no THE or A in Japanese, it does not mean we can do without in English. Since there is no plural in Japanese, it does not mean everything is to be translated as singular.

or consider it this way:

the sound of water ... chokuyaku this to Japanese..

?? oto no mizu ? certianly not !

Discussion of direct translations

Translating Haiku Forum

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

old pond . . .

frog leaps into

water’s sound

old pond . . .

a frog leaps in

water’s sound

© William J. Higginson, Haiku by the Numbers. An Essay.

Here I feel like asking, does the frog jump into the sound?

Is there a sound before the frog jumps?

Re-arrangeing the original Japanese, I start again:

Furuike ga arimasu.

Kawazu ga tobikomu to mizu no oto o kikoemasu.

There is an old pond.

As the frog/the frogs jump/leap/plunge in,

I/we hear the sound/the noise of the water.

These are the facts. How to state them short, but poetically?

an old pond -

the sound of water

when the frogs jump in

or to keep the line order in the translation

this old pond -

as the frogs jump in

the sound of water

This is the situation in my rural Japan, where the frogs are never alone, but with the extended family of a few hundred. All start quaaaking at a certain point, then shut up again, then quaaaaking again. And suddenly, they all leap into the irrigation pond.

Look at some of my FROG haiku,

edited by KAWAZU himself !!!

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

You can also find this spelling:

In attempt to imitate the one line of a Japanese haiku:

furuikeyakawazutobikomumizunooto

... this is of course nonsense. So is this:

FURUIKEYA KAWAZUTOBIKOMU MIZUNOOTO

mizunooto > mizunoo to

Mizunoo, Mizu no O, he was an emperor of Japan ! 後水尾天皇

Spelling Japanese, the Hepburn System

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Water of Sound, a problem

You can also google for this translation in the internet

Old pond!

frog jumps in

water of sound.

water of sound ... well ...

For many of us, an absolute indicator of a haiku is a break or caesura either at the end of the first or second line.

old pond

a frog leaps into

the water of sound

http://www.ahapoetry.com/haidefjr.htm

www.ahapoetry.com/haiku.htm

... ...

a translation done word by word from the Japanese original. In the phrase "water of sound" you get to see the form of post position in Japanese which is an inversion of what we call in English pre position or preposition. In his commentary that follows each poem, because of the three forms he is able to discuss the various multiple meanings of each Japanese word and allow the non-Japanese reader to enter the world of Basho in a way that would else not be possible.

Some English reader called reading a book of haiku like "being pecked to death by doves." Said reader felt attacked by the short choppy verses and was apparently not able to get into the spirit of play that the authors infused their verses with.

http://www.doyletics.com/arj/azwrvw.htm

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Jumping into the Sound, a problem

Compiled by Larry Bole

Here is an interesting footnote to an essay, "The State of Modern Japanese Literature," by Okuizumi Hikaru (which appeared in "Japanese Book News Number 46"):

"In a book published this year titled 'Furuike ni kawazu wa tobikonda ka' [Did the Frog Jump into the Pond?] (Kashinsha, 2005), the contemporary haiku poet Hasegawa Kai puts forward the new hypothesis that the frog did not, in fact, leap into the water."

http://www.jpf.go.jp/j/publish_j/jbn/pdf/jbn46.pdf.

For those interested, at this year's Haiku North America 2007, taking place from Wednesday, August 15, to Sunday, August 19, in Winston- Salem, North Carolina, Dr. Richard Gilbert will be giving the following presentation:

Did the Frog Jump Into the Old Pond?

A presentation by Dr. Richard Gilbert. Several literary and cultural elements of haiku which Basho instituted are now just beginning to come to light, as Hasegawa Kai discusses, in "Did the Frog Jump Into the Old Pond?" (furuike ni kawazu wa tobi konda ka, 2005).

Hasegawa Kai wrote :

"And now, the next question is,

what kind of information was it that was written here?

First it was written that Basho and his disciples heard frog-jumping sounds; in other words, if Basho had seen frogs jumping into the water he would have written what he had seen (not heard).

Instead, he wrote of the sounds that met his ear.

This means that Basho hadn't seen frogs jumping into water. We can imagine Basho in his hermitage Basho-An (in Fukagawa, Edo), listening to the sound of frogs jumping into water, heard outside.

Another important fact is

that when we read the poem, we image the ku happening in the order in which it is read; but, in fact, it was first written just as (the phrase). Moreover, sometime after, the phrase was 'capped' to complete the composition of this ku.

So, this ku is not in reality consecutive."

Matsuo Basho created a hokku style which introduced radically disjunctive acts of "cutting through" realism in order to express consciousness. Yet due to an overemphasis on the direct image and other factors, Basho's achievement lies partially concealed, in Japan and elsewhere. As Hasegawa's work has not been made available in English, his freshly creative insight provides enticing bridges to shared and deepened understanding.

from haikunorthamerica.com/hna_2007_events.html

From the UVa Library Etext Center: Japanese Text Initiative:

"The frog in the old pond appearing in a famous Bashoo's haiku is a "king frog", or a "ground frog" , which has a tendency to hastily jump into the water when it hears footsteps."

http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/japanese/haiku/long.xsl&clear-stylesheet-cache=yes&entryid=kawazu

Found at answers.com (apparently borrowed from the Wikipedia article on Basho):

"In early 1686 he composed one of his best-remembered hokku:

furuike ya / kawazu tobikomu / mizu no oto

the old pond / a frog jumps in-- / water's sound [1686]

Apparently this poem became instantly famous: by April the poets of Edo gathered at the Basho Hut for a haikai no renga contest on the subject of frogs that seems to have been a tribute to Basho's hokku, which was placed at the top of the compilation."

http://www.answers.com/topic/matsuo-bash-1

A reference to a partial German translation, from an essay, "Ecstasy of the Moment and the Depth of Time," by Dusan Pajin (Yugoslavia):

"We leave aside the point noted by [Raoul] Hausmann (1963), who translated the last stanza [sic] as "vertieft das Schweigen" (deepening the silence)."

Ein uralter Weiher:

Der Sprung des Frosches

Vertieft das Schweigen.

Der alte Weiher:

Ein Frosch, der grad hineinspringt -

Des Wassers Platschen ...

http://www.tempslibres.org/aozora/en/hart/hart10.html

A few thoughts of my own: some translators translate

"furuike" as "quiet pond."

I think this makes the haiku too two-dimensional, focusing solely on the silence/sound dichotomy.

And then there is the question of whether it is one frog jumping or many. Most translators into English, and the few Japanese commentaries I have seen translated into English, tend to make it out to be one frog. But others have said that in real life, there would be more than one frog.

I say how about both one and many, as the haiku poet Wakyu suggests:

hitotsu tobu oto ni mina tobu kawazu kana

At the sound of one jumping in,

All the frogs

Jumped in.

trans. Blyth

Compiled by Larry Bole

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Quote from Straw Hat, by Tateo Fukutomi

Why, then, do so many translators of haiku feel that they have carte blanche privileges vis-à-vis the ordering of words and the images evoked by them? Of course, slavishly literal translations are inadvisable, since, to cite just one structural difference between Japanese and English, the Japanese equivalent of “of” (no) is postpositional, coming after a noun or noun phrase, whereas the English “of,” as we all remember from elementary school, is prepositional. Mizu no oto or, literally, “water of sound,” idiomatically translates as “sound of water,” or even better, as Alan Watts rendered Bashô’s famous use of the phrase: “plop ! ”

In my view, a poet of haiku — or any poet, for that matter — has his or her pretty good reasons for beginning with Image A and ending with Image B. Bashô could have easily written: “Sound of water — the frog jumps in the old pond” ... but he didn’t. He chose, of course, to cap this particular haiku with mizu no oto (Watts’s “plop !”), following the image of the old pond, not preced- ing it.

If a haiku is a little journey of mind and spirit from an old pond to a frog’s splash in the water, the translator who capriciously turns this around is writing a completely different poem, and a bad one at that. Matters order image!

David Lanoue

http://www.modernhaiku.org/bookreviews/Fukutomi2005.html

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Traces of Dreams

Haruo Shirane

According to one source, Kikaku (1661-1707), one of Basho's disciples, suggested that Basho use yamabuki ya (globeflower!) in the opening phrase, which would have left Basho's hokku within the circle of classical associations.

Instead Basho worked against what was considered the "poetic essence" (hon'i), the established classical associations, of the frog. In place of the plaintive voice of the frog singing in the rapids or calling out for his lover, Basho gave the sound of the frog jumping into the water. And instead of the elegant image of a frog in a fresh mountain stream beneath the globeflower, the hokku presented a stagnant pond. Almost eight years later, in 1789, Buson (1716-83), an admirer of Basho, offered this poetic meta-commentary.

jumping in

and washing off an old poem --

a frog

tobikonde furu-uta arau kawazu kana

jumping-in old-poem wash frog !

Basho's frog, leaping into the water, washed off the old associations of the frog with classical poetry, thus establishing a new perspective. At the same time, Basho's hokku gave a fresh twist to the seasonal association of the frog with spring: the sudden movement of the frog, which suggests the awakening of life in spring, stands in contrast to the implicit winter stillness of the old pond."

source : Happy Haiku Forum quote

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Makoto Ueda wrote:

Master Basho was at his riverside hut in the north of Edo that spring. Through the soft patter of rain came the throaty cooing of doves. The wind was gentle, and the blossoms lingered.

Late in the third month, he often heard the sound of a frog leaping into the water. Finally an indescribable sentiment floated into his mind and formed itself into two phrase:

a frog jumps in,

water's sound

Kikaku, who was by his side, was forward enough to suggest the words

"the mountain of roses" for the poem's beginning phrase, but the Master decided on "the old pond".

Shiko commented

"I think that although "the mountain roses" sounds poetic and lovely,

the old pond has simplicity and substance."

Gabi's comment

the mountain of roses ... does seem a strange translation for the plant, yamabuki, mountain rose.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

A frog jumped into an old pond of mossy water making a little sound.

The momentary action and the lingering sound remind us of the wonder of a moment and eternity.

Into the old pond

a frog jumped

with a splash

- translated by Kimiyo Tanaka

Until quite recently I just translated like above, but I have realized that as Basho said in this haiku,"furuike ya", "furuike"is "pond" and "ya" is a Japanese cutting word, I should not have translated "into the old pond", but I should cut after the old pond. BesidesBasho did not actually see a pond, he saw an old pond in his mind.

So I would like to change my translation. I am not sure whether some other poets translated like this or not....

The Pleasure of Haiku, by Kimiyo Tanaka

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Initiator of “Sound” of Nature

..... both poems turn on the transformative power of a sound of

nature, a sound initiated by a small, powerless creature, a frog and a cicada. We are almost certain that it is not by chance that Basho used these two creatures in these two haiku which express a very similar theme.

There is a Chinese idiom, 蛙鸣蝉噪 wa ming chan zao , which literally means

“frog . cry - cicada . noise.”

That is, frogs and cicadas are considered to be noisy, loud, and annoying. Hence, this saying, when it is used to refer to texts or arguments, means loud arguments and texts of poor-quality.

Basho, known as having profound knowledge of Japanese and Chinese classics, would have been aware of this Chinese idiom.

source : Hiraga and Ross, 2007

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

A daoist might approach something like Basho's subject-object free, self-referencing haiku of the frog and the old pond (although, as a game, one may always cheat to find a subject everywhere.

For example,

compared to whom is the old pond old?

The frog, presumably.)

The daoist reads the haiku, searching for inspiration, and to his surprise he is mesmerized by the complete emptiness and disregard of anything outside the poem's subject matter. ... the daoist finds himself in a loop of recognition with the poem,

and in its emptiness he does not find the old pond or the frog,

but instead he finds the complete lack of anything else.

It is just a simple, emotionless “plop” of water

as the frog jumps in.

No Ego, no emotions, only … “plop”

The Daoist, the Frog and the Pipe

. Gestur Hilmarsson .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

furuike / ya / kawazu / tobikomu / mizu / no / oto

old-pond / : / frog / jump-in / water / 's / sound

http://billknott.typepad.com/billknott/2006/05/mizu_no_oto_som.html

Matsuo Basho's Frog Haiku (30 translations)

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Quoting Larry Bole

Regarding Basho's frog: there certainly has been a lot of interpretive commentary written about it. It doesn't appear that there are any "simple answers."

Nevertheless, Shiki wrote an essay about Basho's frog, which has been translated by Blyth in "A History of Haiku," Vol. 2, (Fourth Printing, 1971), pp. 46-76, in which Shiki says:

...a visitor ... said to me, "This verse is called a masterpiece, known even by uneducated people such as pack-horse men and servantmen, yet no one can explain the meaning." As he wanted me to explain it, I answered, "The meaning of this verse is just what is said; it has no other, no special meaning. ... it only means that he heard the sound of a frog jumping into an old pond - nothing should be added to that.

If you add anything to it, it is not the real nature of the verse. Clearly and simply, not hiding, not covering; no thinking, no technique of words, - this is the characteristic of the verse. Nothing else."

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Quote from G. Blankestijn

Kiyosumi Garden Pond

Haiku Memorial Stone

Those fish ponds of course do not exist anymore, but there is a large pond in the Kiyosumi Gardens not far from the Basho Museum. Not surprisingly, one of the three frog-and-pond haiku stones stands right in this garden. In the expectation that this pond will help me to evoke the proper atmosphere I proceed to the Kiyosumi Gardens.

Basho wrote the frog haiku in 1686. The circumstances under which this took place were recorded by his disciple Kagami Shiko (1665-1731), in Kuzu no Matsubara ('Pine Forest of Kuzu,' 1692), a book written to elucidate Basho's idea of haikai.

Basho was sitting in his riverside hut. It was spring. A soft drizzle fell and the smell of blossoms was in the air. Mountain roses were blooming at the edge of a pond in the garden. Enomoto Kikaku (1661-1707) kept Basho company, but master and disciple were both sitting quietly. Suddenly a frog jumped into the old pond, breaking the stillness with a watery plop. In Basho's mind, two phrases formed, the last part of a hokku:

a frog jumps in

sound of water

Kikaku suggested yamabuki ya, 'mountain roses' for the first five syllables. In traditional poetry, this plant was associated with frogs. Basho pondered for a while and then decided to use instead a phrase uncommon in poetry: 'the old pond,' furu ike ya. This was a nice literary twist which added 'newness' and 'lightness' to the poem. It was also the utmost of simplicity.

Basho's frog was an experimental one. It was the first silent frog in Japanese poetry, which so far had been regaled with quaking choruses. Instead of this night music, Basho's frog exits with a soft plop, after which rings of water expand and die out. It is a bit lonely, just like Basho.

By the way, the frog can also be plural, as the Japanese language normally does not make numerical distinctions. But to have a whole army of frogs jump into the pond seems just too noisy. It does not fit the atmosphere of the poem, which is one of yugen, of stillness, symbolized in the pond that after all is an ancient one. This is something almost all translators agree on.

The mizo no oto or 'sound of water' is another matter. Many translators cannot resist the temptation to enliven this phrase by translating it as 'Plop,' 'Splash,' or even 'Kdang.' That is strictly speaking not correct, for Basho himself could also have used an onomatopoeic word. The Japanese language is very rich in them, more so than English, but Basho purposefully selected 'sound of water,' perhaps to emphasize the progression from stillness (no sound) to movement (sound) to stillness again.

Zen-master and graphic artist Sengai (1751-1837) wrote a parody of the frog haiku (yes, already in Edo-times it was so popular that it invited parodies!) in which he creates a comic effect by using the onomatopoeic pon to, resulting in a very different poem:

old pond

something plop

jumped in

furuike ya naniyara pon to tobikonda

Copyright © 2003-2006 Ad G. Blankestijn,

Japan. All rights reserved.

http://www.xs4all.nl/~daikoku/haiku/meguri/kuhi-2.htm

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

A Contrarian View on Basho's Frog Haiku

Now, why do I say that Basho's frog haiku is one of the most misunderstood haiku poems? Possible misunderstandings about this haiku include:

We seldom see in Japan a single frog, rather many of them around a pond, rice paddies or any other similar places in spring time as it is the season for their mating. They are noisy and in abundance. Why should it then, be a single frog and not a number of, or many frogs?

Only three translations refer to “frogs” out of 100 in Sato. Who decided it was only one frog? If we have an open mind, it would be either frogs (plural), which is the most natural interpretation, or at least a single frog but only as a literary device to represent many frogs (which is often the case in Japanese poems or paintings). Though there is a tradition in Japan and China to have a single subject/object such as kogan (a lone goose) or ikken-ya (a lone house) as an artistic or poetic technique, there is no reason to believe why Basho’s haiku should be talking about a lone frog. The fact that the two known haiga in Basho’s hand depict only one frog is not really a definitive proof that he meant one frog in the poem, though it is a strong possibility. They are only drawings, or even doodles, whereby his inclination was to draw only one frog whatever the reason (it could be that his drawing skill then was not good enough to draw a lot of frogs, as the frog is poorly drawn. We simply do not know it). He could well have drawn more than one frog on other occasions like he did with the crow-perching-a-withered-branch haiku whereby he drew more than one crow.

Frogs tend to jump into the water one after another, or simultaneously in spring time. Why should it be a single splash? If it is in other seasons, they may jump into the water more intermittently.

As has been mentioned, frogs are noisy in spring, when this haiku is believed to have been composed, because of the mating season. They are a symbol of the merriment, colour, noises, life (sex) and bustling movements of spring—a celebration of life on earth. Take the kigo, kawazu-gassen for example. This is a kigo which depicts many frogs mating in spring, but specifically many males mounting a single female on top of each other. They fight and jostle for the female and that is why the word gassen (kassen), or battle or fight is used. A battle among male frogs cannot be quiet or peaceful.

Why, then, should the scene of Basho’s haiku be doctored and philosophised into one of stillness, loneliness, quietude and tranquillity? Does it not sound too good to be true? There are many factors which can be attributed as having contributed to this popular interpretation of the frog haiku, ranging from serious factors to nonsensical speculations. They form the other side of the coin of what I am raising as forgotten or neglected questions in this article. Therefore, in order to understand this coin fully we need to look into them again but that will need another article.

...

Firstly, it should be noted that Basho did not always write his poems in situ from direct experiences. Nor did he keep his original poems unchanged and unrevised. On the contrary, it is known that he wrote some of his poems after the event (sometimes long after the event) and that it was his practice to revise (suiko) his poems, often not just once but several times. To write a haiku while you are directly experiencing something, or at least soon after—is a teaching of kyakkan-shasei (or objective sketch from life) from the later Shiki-Kyoshi school—taken a little too far. In Basho’s mind, there were ideas or ‘phrases’ (part of a haiku which he composed in his mind) at any given time. Also, even if he had written a haiku, it was lingering in his mind afterward for a long time if he was not completely satisfied with it. True, he was teaching that haiku should be written within a certain short period of time, i.e. relatively quickly. If one cannot do so, he taught, one should throw it away into the dustbin. However, this is slightly different from doing the suiko (revision).

So, it is wrong to assume, let alone conclude, that Basho wrote the frog haiku in situ or even from direct experience.

Read the full article here:

© Susumu Takiguchi - WHR

*****************************

Worldwide use

India

breeze leads on

the endless sunny path ~

sound of a stream

Quoted from Wonderhaikworlds: Lux and Narayanan

*****************************

Things found on the way

Here is a collage made by 5 year olds at Newton Aycliffe Primary School.

It came from them after me telling the story of Basho and showing them his frog poem.

We started with it in Japanese - then i told them that there were many different translations and shared a few.

Then asked them to come up with their version - and it mirrors many versions that children come up with.

Paul Conneally, July 2006

*****************************

HAIKU

wondering what it

would be like to jump into

the sound of water?

Robert Wilson

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Kare eda ni/ Karasu no tomari/ Mizu no oto

Ancient pond

A frog leaps in

The sound of the water

(Tr. Donald Keene)

http://www.lifepositive.com/Mind/arts/new-age-fiction/satori.asp

I hope this is just a wrong quote. The third line should be : aki no kure

on a withered branch a crow has settled - autumn evening

ooo ooo ooo ooo ooo ooo ooo ooo ooo ooo ooo

© Haiga by Shane Gilreath, July 2006

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

old pond

if basho was here

i'd jump in to!

anonymous (let me know the author !!!)

.... What is the sound

.... of one frog jumping?

.... [haiku]

<><><> Chibi

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

The Mozart Haiku

Trial by water -

Leaping into the dark pond

Startled by the flute.

The Punk Haiku

Fuckin' Friggin' Frog

Jumpin' from the soddin' pad

Who gives a shit!

and many more MUSIC frog haiku versions :

source : bonsai/music.html

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

In my rural Japan, there are many frogs jumping the old irrigation ponds in the season when the paddies are filled with water, like now in May.

For the sake of argument, let us see the pond as my mind/soul/heart, the frogs as worldly desires, illusions, delusions (bonno), then we get

my quiet meditating mind -

as desires arise (jump in),

the sounds of the world unfold

Terraced Rice Paddies in my Valley

a thousand old ponds -

a million frogs jumping -

a billion echoes

Gabi Greve, May 2007

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

the old pond "stands for" an old pond

David Landis Barnhill

. Hon-I, Symbols, Images and Hokku .

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Basho and the SOUND OF WATER

松風の落葉か水の音涼し

matsukaze no ochiba ka mizu no oto suzushi

is it the wind

among the falling pine needles?

the sound of water so cooling

(1685)貞亨元年

furu-ike ya kawazu tobikomu mizu no oto

(1686) 貞亨3年

.................................................................................

楽しさや青田に涼む水の音

tanoshisa ya aota ni suzumu mizu no oto

how pleasant -

cooling off among green fields and

the sound of water

(1688) 元禄元年夏『笈の小文』

After the rainy season, drinking with friends in the evening, cooling off from a warm summer day.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

元日やされば野川の水の音

ganjitsu ya sareba nogawa no mizu no oto

New Year's Day -

the sound of water

from a creek

Konishi Raizan 小西来山(1654 - 1716)

*****************************

Related words

One Hundred Frogs ... the story continues

***** Matsuo Basho and his memorial day, Basho-Ki

松尾芭蕉 と 芭蕉忌

kigo for early winter

***** . Pond, little lake (ike 池) ...

kigo for various seasons

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

the sound of xxx の音

kigo

aki no oto 秋の音 "sound of autumn

aki no koe 秋の声 "the voice of autumn"

fuurin no oto 風鈴の音 sound of a wind chime

hatsuneuri, hatsune uri 初音売 first vendor of a nightingale flute

mochi no oto 餅の音 sound of (pounding rice for) mochi

shamisen no oto 三味線の音 sound of a shamisen

taki no oto - 滝の音 sound of a waterfall

umi no oto 海の音 sound of the sea

yukidoke no oto 雪解けの音 sound of snow melting

OTHERS

ame kiri no oto 飴切りの音 sound of cutting sweets

hashi no oto 橋の音 sound of a bridge

kane no oto 鐘の音 sound of a (Japanese temple) bell

kaze no oto 風の音 sound of wind

and . kumo no oto 雲の音 sound of clouds

and . oto wa shigure ka . haiku by Santoka

shizukesa no oto 静けさの音 sound of silence

xxx no koe - voice of an animal

Kirine 霧音 "sound of fog" - is a woman's name

Kiri no Oto 霧の音 "sound of fog"

is the title of a book by 眞海 恭子

source : amazon.com

[ . BACK to Worldkigo TOP . ]

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

18 comments:

.

> !dnop dlo nA

> -ni spmuj gorf A

> .retaw fo dnous ehT

--Basho, Matsuo (1644-1694)

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/cherrypoetryclub/message/28348

I don't know how the Japanese "works" , but here are some word-for-word translations:

furu-ike | ya | kawazu | tobi-komu | mizu-no-oto

Harold Henderson:

old-pond | : | frog | jump-in | water-sound

Makoto Ueda:

...............................| mizu | no | oto

old-pond | : | frog | jump-in | water | 's | sound

Haruo Shirane gives the same word-for-word translation as Ueda.

David Barnhill translates "ya" with an exclamation point instead of a colon, but otherwise he translates word-for-word the same as Ueda and Shirane.

"Water's sound" doesn't sound very evocative in English. To me, it

almost sounds like a science report. Translators get creative when they decide how to translate "mizu no oto." The translation you have quoted says "plunk."

Surprisingly to me, Henderson stays with "water-sound." Ueda

says "water's sound." Shirane goes more formal, saying "the sound of

water." Barnhill sticks with the literal "water's sound."

Some translators have substituted "noise" for "sound." Not much difference there to me.

Other onomotopoetic English words that have been used for "mizu no

oto" are "splash," "splosh," "plash," "plop," "kdang," "kerplunk,"

"kersplat," "ploomp," and "blip." I suspect there are probably more.

Some translators get around the problem (if it is a problem) by not

specifying a sound at all, but leaving it up to the reader's

imagination, with variations on, "listen--a frog jumps into the

water."

Larry

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/happyhaiku/message/4560

For what it's worth, there is another interpretation of this haiku.

Some translators argue that the "a-ha" or whatever of this haiku is that the frog isn't CAUSING the sound, but ENTERING the sound.

The lines literally mean that the frog is entering the SOUND OF WATER and not causing a splash, but simply joining in what was already there.

At the ancient pond

a frog plunges into

the sound of water

(Hamill)

.....

furuike-ya kawazu tobikomu mizu-no oto

The ancient pond...

a frog jumps in

the sound of water

_Basho

The -mu in tobikomu actually acts as a period in archaic Japanese not to signify a modifier as it does in modern Japanese. So in modern Japanese the kawazu tobikomu mizu-no oto would read as "a frog jumps in(to) the sound of water" whereas in archaic Japanese it reads as

"a frog jumps in. the sound of water".

Another possibility is "the ancient pond.... a frog, jumps in the sound of water".

Of the above Basho can almost certainly have been thought to have made the haiku as in the middle example.

The "jumping in sound" concept was probably first thought of by a person (whether Japanese or Western) who didn't understand archaic Japanese to the point that they should have to be translating.

Dhugal Lindsay

http://haiku.cc.ehime-u.ac.jp/shiki.archive/9507/0341.html

Why did Basho choose to write "mizu no oto" for the last line of his most famous haiku, rather than something more onomatopoeic in Japanese?

Here is Ad G. Blankestijn's comment on this:

The mizo [sic] no oto or 'sound of water' is another matter. Many translators cannot resist the temptation to enliven this phrase by translating it as 'Plop,' 'Splash,' or even 'Kdang.' That is strictly speaking not correct, for Basho himself could also have used an onomatopoeic word. The Japanese language is very rich in them, more so than English, but Basho purposefully selected 'sound of water,' perhaps to emphasize the progression from stillness (no sound) to movement (sound) to stillness again.

Zen-master and graphic artist Sengai (1751-1837) wrote a parody of the frog haiku (yes, already in Edo-times it was so popular that it invited parodies!) in which he creates a comic effect by using the onomatopoeic pon to, resulting in a very different poem:

old pond

something plop

jumped in

furuike ya | naniyara pon to | tobikonda

http://www.xs4all.nl/~daikoku/haiku/meguri/kuhi-2.htm

So this is what Basho's haiku might have looked like instead:

furu ike ya kawazu tobikomu pon to kana

or something like that! LOL

But, and here is my speculation, this altered version doesn't SOUND as good in Japanese as the original. Although in Japanese a frog's croak is "gero gero" (just as in English a frog's croak is "ribbit"), I get the impression of a frog croaking when I hear the haiku outloud. In any event, there is certainly a musicality in the original, with all those "u" sounds, sometimes accompanied by a

beginning "z", and the "o" sounds, especially at the end, where they 'sound' like the wave-ring on the water, made by the frog's jump, widening out and fading away...

And I like the way the beginning "u" sounds 'open out' with "ya kawa..." as if representing the way a frog's body 'opens out' as it

goes from squatting to leaping.

This haiku of Basho's definitely 'rolls off the tongue!'

Larry

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/translatinghaiku/message/1585

Dead Pond

Jumping Frog

Sound of Water

In a (heretofore) Lifeless (complete stillness) Pond (Universe)

A Jumping Frog (Life)

Makes a Quick Splash

Translation:

Life is just a brief interruption in the great stillness of nirvana.

Basho first wrote:

kawazu tobikomu

mizu no oto

and then spent a year and a half deciding on the first line.

Thus, that little 'ya' is far from trivial. It is 'lifeless' pond or dead pond (to be blunt).

You avoided that pesky little detail of the okurigana which compliments, though also limits, the cognitive content of the Kanji.

Best regards,

O-cha-ryu

Quote from

http://www.bopsecrets.org/gateway/passages/basho-frog.htm

Bureau of Public Secrets

(Thirty Translations and One Commentary)

Commentary by Robert Aitken

THE FORM

Ya is a cutting word that separates and yet joins the expressions before and after. It is punctuation that marks a transition — a particle of anticipation.

Though there is a pause in meaning at the end of the first segment, the next two segments have no pause between them. In the original, the words of the second and third parts build steadily to the final word oto. This has penetrating impact — “the frog jumps in water’s sound.”

Haiku poets commonly play with their base of three parts, running the meaning past the end of one segment into the next, playing with their form, as all artists do variations on the form they are working with.

Actually, the name “haiku” means “play verse.”

COMMENT

This is probably the most famous poem in Japan, and after three hundred and more years of repetition, it has, understandably, become a little stale for Japanese people. Thus as English readers, we have something of an edge in any effort to see it freshly. The first line is simply “The old pond.” This sets the scene — a large, perhaps overgrown lily pond in a public garden somewhere.

We may imagine that the edges are mossy, and probably a little broken down. With the frog as our clue, we guess that it is twilight in late spring.

This setting of time and place needs to be established, but there is more. “Old” is a cue word of another sort. For a poet such as Bash・ an evening beside a mossy pond evoked the ancient. Basho presents his own mind as this timeless, endless pond, serene and potent — a condition familiar to mature Zen students.

In one of his first talks in Hawai’i, Yamada Koun Roshi said: “When your consciousness has become ripe in true zazen — pure like clear water, like a serene mountain lake, not moved by any wind — then anything may serve as a medium for realization.”

D.T. Suzuki used to say that the condition of the Buddha’s mind while he was sitting under the Bodhi tree was that of sagara mudra samadhi (ocean-seal absorption). In this instance, mudra is translated as “seal” as in “notary seal.” We seal our zazen with our zazen mudra, left hand over the right, thumbs touching. Our minds are sealed with the serenity and depth of the great ocean in true zazen.

There is more, I think. Persistent inquiry casts that profound serenity. Tradition tells us that the Buddha was preoccupied with questions about suffering. The story of Zen is the story of men and women who were open to agonizing doubts about ultimate purpose and meaning. The entire teaching of Zen is framed by questions.

Profound inquiry placed the Buddha under the Bodhi tree, and his exacting focus brought him to the serene inner setting where the simple incident of noticing the morning star could suddenly disclose the ultimate Way. As Yamada Roshi has said, any stimulus would do — a sudden breeze with the dawn, the first twittering of birds, the appearance of the sun itself. It just happened to be a star in the Buddha’s case.

In Basho's haiku, a frog appears. To Japanese of sensitivity, frogs are dear little creatures, and Westerners may at least appreciate this animal’s energy and immediacy. Plop!

“Plop” is onomatopoeic, as is oto in this instance. Onomatopoeia is the presentation of an action by its sound, or at least that is its definition in literary criticism. The poet may prefer to say that he became intimate with that sound. Thus the parody by Gibon Sengai is very instructive:

The old pond!

Basho jumps in,

The sound of the water!

Hsiang-yen Chih-hsien became profoundly attuned to a sound while cleaning the grave of the Imperial Tutor, Nan-yang Hui-chung. His broom caught a little stone that sailed through the air and hit a stalk of bamboo. Tock!

He had been working on the koan “My original face before my parents were born,” and with that sound his body and mind fell away completely. There was only that tock. Of course, Hsiang-yen was ready for this experience. He was deep in the samadhi of sweeping leaves and twigs from the grave of an old master, just as Bash・is lost in the samadhi of an old pond, and just as the Buddha was deep in the samadhi of the great ocean.

Samadhi means “absorption,” but fundamentally it is unity with the whole universe. When you devote yourself to what you are doing, moment by moment — to your kn when on your cushion in zazen, to your work, study, conversation, or whatever in daily life — that is samadhi. Do not suppose that samadhi is exclusively Zen Buddhist. Everything and everybody are in samadhi, even bugs, even people in mental hospitals.

Absorption is not the final step in the way of the Buddha. Hsiang-yen changed with that tock. When he heard that tiny sound, he began a new life. He found himself at last, and could then greet his master confidently and lay a career of teaching whose effect is still felt today. After this experience, he wrote:

One stroke has made me forget all my previous knowledge.

No artificial discipline is at all needed;

In every movement I uphold the ancient way

And never fall into the rut of mere quietism;

Wherever I walk no traces are left,

And my senses are not fettered by rules of conduct;

Everywhere those who have attained to the truth

All declare this to be of highest order.

The Buddha changed with noticing the morning star — “Now when I view all beings everywhere,” he said, “I see that each of them possesses the wisdom and virtue of the Buddha . . .” — and after a week or so he rose from beneath the tree and began his lifetime of pilgrimage and teaching.

Similarly, Basho changed with that plop. The some 650 haiku that he wrote during his remaining eight years point precisely within his narrow medium to metaphors of nature and culture as personal experience. A before-and-after comparison may be illustrative of this change. For example, let us examine his much-admired “Crow on a Withered Branch.”

On a withered branch

a crow is perched:

an autumn evening.

kare eda ni

Withered branch on

karasu no tomari keri

crow’s perched

aki no kure

autumn’s evening

The Japanese language uses postpositions rather than prepositions, so phrases like the first segment of this haiku read literally “Withered branch on” and become “On [a] withered branch.”

Unlike English, Japanese allows use of the past participle (or its equivalent) as a kind of noun, so in this haiku we have the “perchedness” of the crow, an effect that is emphasized by the postposition keri, which implies completion.

Basho wrote this haiku six years before he composed “The Old Pond,” and some scholars assign to it the milestone position that is more commonly given the later poem. I think, however, that on looking into the heart of “Crow on a Withered Branch” we can see a certain immaturity.

For one thing, the message that the crow on a withered branch evokes an autumn evening is spelled out discursively, a contrived kind of device that I don’t find in Basho #146;s later verse. There is no turn of experience, and the metaphor is flat and uninteresting.

More fundamentally, this haiku is a presentation of quietism, the trap Hsiang-yen and all other great teachers of Zen warn us to avoid. Sagara mudra samadhi is not adequate; remaining indefinitely under the Bodhi tree will not do; to muse without emerging is to be unfulfilled.

Ch’ang-sha Ching-ts’en made reference to this incompleteness in his criticism of a brother monk who was lost in a quiet, silent place:

You who sit on the top of a hundred-foot pole,

Although you have entered the Way, it is not yet genuine.

Take a step from the top of the pole

And worlds of the ten directions will be your entire body.

The student of Zen who is stuck in the vast, serene condition of

nondiscrimination must take another step to become mature.

Basho's haiku about the crow would be an expression of the “first principle,” emptiness all by itself — separated from the world of sights and sounds, coming and going. This is the ageless pond without the frog. It was another six years before Bash・ took that one step from the top of the pole into the dynamic world of reality, where frogs play freely in the pond and thoughts play freely in the mind.

The old pond has no walls;

a frog just jumps in;

do you say there is an echo?

Leap Year of the Frog 2008

leap day -

the haiku frogs jump

to new hights

Gabi

old pond/frog(s) jumping-in water's sound.

Literal translation by Kai Hasegawa

My first thought is how is this poem not realism? I'm just started to get interested in poetry so I don't speak the lingo.

If realism is defined as "compositions based only upon those things you have directly seen", then this could certainly fit that definition. Although I realize it predates the school of realism.

I'm guesstimating that this haiku goes beyond realism because there is something timeless, eternal, of stillness about it. If the pond represents stillness and the frog's jumping represents action, then the sound of the water is where stillness and action meet. I'm sure I'm not explaining this well but the scene described in the poem transcends, it has a deeper meaning.

While I was out for a walk, I came up with another meaning for the poem. Unfortunately I don't recall how I got here but the old pond maps to eternity and the frog an individual person. It suggests that our lives are as transient and as beautiful as the sound made by a frog as it jumps into the water.

So, I'm guessing that realism does not go beyond what it objectively sees; realism does not transcend.

Judy

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/simply_haiku/message/21777

you listen too, because that sound is not even a splash and so brief very hard impossible to sound locate, and the ripples are gone by thge time you have the direction. By the time the brain processes the "sound of water" it's lost the immediacy of the silence.

And especially, there is a cut between pond and fog, so IMHO, to my ear, stopping to process "the sound of water" creates in English a second cut between frog and sound, a cut not in the Japanese I am told, and the whole point is the interdependant co-arising of frog and silence: it's the continuity of transformation of frog into silence, return of frog to silence. So cutting off the sound from the frog and from the pond decimates the verse.

I awaken to the reality of frog is silence, pond is silence... all exists in the unity of pond without seperation, without distance, without pause stop thought. The first cut, between frog and pond are trancended by their unity in the silence which we hear only because of that subtle frog. A frog who's disappeared before we even see it, or even see its ripples. Their existence itself makes the silence real and their absence real.

Existence and non-existence are not two.

If you cut the sound from the frog, all of that interdependant co-arising is cut.

I can't believe Basho was so clumsy. I have to believe his Japanes must stitch his frog into its silent sound.

Also, as a country boy I hear all those frogs and their predator avoidance behavior. Frogs are tasty. And they prefer to leave your mouth tasting nothing. The silence is also the taste of no frog for dinner.

isa

old pond

a frog leaps in

ah, water's sound

sheila

>1、古い時代、「かはづ」と「かえる」はどう区別されていたのか?

歌語(かご)と古語と俗語

「主として和歌をよむ時だけに用いる言葉。鶴(つる)に対する「たづ」、蛙(かえる)に対する「かはづ」など」(小学館「国語大辞典」)

1)かはきぎす(川雉(子))

川で「きぎ」と雉(きじ<古名>ぎぎし/きぎす)のように鳴く河鹿蛙/かわず。別名:金襖子(きんおうし)/錦襖子(きんおうし)/石鶏(せきけい)。(東京堂「類語辞典」)

2)かはづ(川津)

万葉集では「鳴川津(なくかはづ)」は「石本去らず(澄んだ川瀬の石の下)」であり、「川津妻(かわづつま)」も「上つ瀬に(澄んだ川上の浅瀬で)」であり、川瀬のとおり澄んだ河鹿蛙の鳴き声が詠われている。(東京堂「古典読解辞典」)

3)かいろ

「牡鹿が雌鹿を恋い慕って鳴く声を、古くは「かひよ(カイヨ)」と聞き取ったが、これを「帰ろ」の意にとりなしていったもの。」(「古語大辞典」)

4)かへら/かへる/かいる(蛙)

蛙の古語、川雉子とも。「田火(でんか)/玉芝(ぎょくし)/風蛤(ふうこう)/活東(かつとう)/かわず」(東京堂「古典読解辞典」)

雄雉のキギと鳴く、あるいは牡鹿のカイヨと求愛する声に近いことから、澄んだ川辺での鳴き声のきれいな蛙を、特にかわづとして歌語にしたものでしょうか。そういう意味からすれば、「蛙の目借時」という季語も、実は川津の雌狩(めかり)、あるいは媾離(めかり)時なのかも知れません。

>2、芭蕉や一茶の時代はどう区別していたのか?

近世前期を代表する俳諧作法書「毛吹草」(岩波文庫)の「巻第三 付合」のリストの中では、「蛙(かへる)」の項には「蛇(くちなは)、梢(こずゑ)、井戸、仙人、月、蜒(なめくじり)」が、一方「樂(がく)」の項に「鶯、蛙(かはづ)、天王寺、住吉、行幸、法事、神前」とある。従って、日常・生活上での蛙は「かへる」であり、特にその音楽的な鳴き声を採るときは「かはづ」ということなのでしょうか。

初蛙/遠蛙/昼蛙/夕蛙などは「かはづ」と読むが、その他の「痩せ蛙」など、その一般的な特徴では「かへる」もしくは「かいる」ということでしょう。

...

http://soudan1.biglobe.ne.jp/qa3066121.html

.

Translation-adaptation by the portuguese writer who lived 30 years in Japan,

Wenceslau de Moraes

(Lisboa, 1854-Tokushima,1929):

A temple, a mossy pond,

Soundless, only cleaved by the sound of frogs

Jumping in the water, nothing else

.

Joys of Japan

old pond –

after jumping

no frog

furu ike ya

sono go tobikomu

kawazu nashi

by Kameda Bōsai (1752 – 1826)

a bored calligrapher and

Confucian scholar.

.

http://www.haigaonline.com/issue9-1/feature/je-p2.htm

.

with a painting

.

"When you hear the splash

Of the water drops that fall

Into the stone bowl

You will feel that all the dust

Of your mind is washed away."

Sen no Rikyu 千利休

1522-1591

Sen Rikyuu, Sen Rikyū 千利休 Sen Rikyu, Sen no Rikyu

Kiyosumi Teien 清澄庭園 Kiyosumi Park

.

https://edoflourishing.blogspot.jp/2018/03/kiyosumi-district.html

.

Post a Comment